Deposit

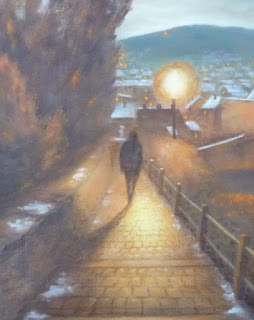

I can’t deny that the toughest years of my life were my childhood and early teenage years. Sure, looking back, some memories have this nostalgic glow, moments that seem simpler and sweeter through the haze of time—simple friendships, easy laughter. But those years were tough in a way that still feels raw. I remember going to the bank with my mom, early on the last day of each month. We'd wake up at six-thirty to head to a faraway bank because it was “deposit day.” Who was depositing what? I didn’t know. All I understood was that someone somewhere was putting some money in mother's account, and that meant we could taste meat that weekend. We’d walk two kilometers from our home in the western neighborhood to the bank near the main market. Taking a taxi was out of the question because every dinar mattered, and if we could save one, it’d go somewhere it was sorely needed. Once we got to the bank, my mom would signal for me to sit on one of the side benches, then head to the counter. I’d sneak glances, trying to understand what was going on, but their voices were too faint for me to catch. My mom would talk to the bank teller, this thick-glassed man with a big belly, an ugly tie, and a mop of uncombed gray hair. I remember his face vividly—it was almost scary to me as a kid. Today, if I could see him, I’d want to punch him as hard as I could and tell him, “I still hate all banks.”

The outcomes of these visits varied. Sometimes, Mom’s face would light up, and I’d see the teller count out some bills, and she’d whisper to me, “Thank God, they deposited.” I’d smile, not fully understanding what “the deposit” meant, or why they’d sometimes refuse. Why wouldn’t they give her what she’d earned if she worked every day, grading papers late into the night after managing a family of five? After those rare good visits, we’d head to the market, where she’d pick up some vegetables and, to celebrate, buy a roasted chicken and some fries. We’d split it, the six of us, into tiny, almost laughable portions. But those bites of chicken, fried or roasted, felt like the world to me. And I still remember Mom’s big smile as she watched us savor that fleeting joy. Other times, it was more of a mixed bag. She’d walk over, and I’d try to sound smart by asking, “Did they deposit?” She’d shake her head, saying, “No, but they gave me an advance.” The bank was bleeding her dry, between loan interest, late fees, and an endless cycle of small advances just to keep her from zeroing out every month. But then, there were the bleakest times, when the conversations would go on, voices would rise, and I’d see my mom stepping back with slow, heavy steps. She’d look at me, whispering, “No deposit.” We’d walk those two kilometers back, empty-handed, ready to start another month of lean meals and starchy staples like pasta, beans, whatever was cheap enough to last us. My mom’s resilience was a miracle, making sure we got through each month without starving. I still remember how we scoured the market for a school uniform we couldn’t afford, only to find a bargain one tucked away in a small store. It was cheap, with a big plastic zipper, and it faded after the first wash. But it was a treasure to me.

I worked in a tomato processing plant to help pay for school, even though the brine left my skin raw and cracked. Then I took on odd jobs with a neighbor, digging wells, fitting pipes, sometimes working in restaurants, one of which fired me because I couldn’t peel potatoes fast enough. All of it is still so vivid in my memory, and I laugh now to bury the urge to cry.

Poverty was relentless, hard, and unforgiving. But my mom was a shield, absorbing the blows so that the pain didn't hit us quite as hard. I realized we were really poor the day I saw her cry over an empty bank balance. Now, when I buy a two-dollar sandwich, I look at it with something like disgust, and think of the kid I used to be. If I could go back in time, I’d bring a bag full of these sandwiches, sit with my mom and siblings twenty years ago, and watch them light up with joy. And I’d laugh, too.

لم أعش الفقر يومًا، ولكنني ألعنه كل يوم. نصك المؤلم دقيق جدًا. الفقر من أبشع صور لعنة الرأسمالية التي تسحق البسطاء. عزائي الوحيد لك هو أمك التي تحملت كل هذا من أجل ابتسامة أطفالها. ربي يحفظها لك.

ReplyDelete